Translation Credibility

A Monolingual Attorney’s Guide to Assessing the Reliability of a Translation

Patent attorneys are increasingly aware that translations can be challenged in litigation, IPR proceedings, and even USPTO prosecution. Even if you are careful to source expert translations for foreign language documents that land on your desk, some cases come with their own translations. Attorneys working on litigation often deal with translations that have been commissioned either by their own clients or the other side’s clients early in the prosecution of a patent, for example, to satisfy IDS requirements. Your clients may also provide their own translations of documents that they consider to be key in the dispute at hand. In other cases, translations may be asserted by an opposing party, with no way for you to determine how credible they are. Fortunately, you do not have to be bilingual to spot potentially unreliable translations. Testing for problems can be fast and painless.

In this three-part series, I’ll talk about ways in which monolingual attorneys can spot dodgy translations of prior art and what needs to be done when you find them. This first post covers some basic “smell tests.” Going forward, I’ll suggest some strategies for translations that fail them.

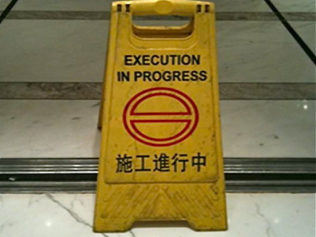

It Doesn’t Rockets Science

The first indication of a dodgy translation is the presence of major grammatical errors. A few odd word choices or unwieldy turns of phrase do not necessarily spell trouble, especially if you have reason to believe that the writer is not a native speaker of English. On the other hand, if rules that you associate with basic literacy are being broken and the grammar is so bad that the document is hard to understand, further investigation is needed.

Although it is common to see translations that were not prepared by native speakers of English, relying on those that are obviously poorly executed carries significant risk. The problem is, if the translator’s command of English is limited, they literally do not know what they are saying. Imagine yourself translating a patent into another language armed with nothing but a dictionary and your high-school (or for that matter, university level) Spanish or French. How confident would you be about submitting your effort to a patent office or a court? In practice, people who do not have a fluent and confident command of the grammar, vocabulary, and colloquialisms of a language not only produce confusing sentences, they almost always simplify or even omit things that are difficult to express. (Yes, that’s right, unskilled translators will actually leave out important parts of a sentence when they don’t know how to say it in the target language.) What is more, they are incapable of evaluating the true meaning of what they write, such that their best effort will never be more than a best guess.

None of this means that an ungrammatical translation is necessarily wrong. The portion of the description that you are interested in may well accurately reflect the source text, but it would be unwise to assume this without checking, especially if a major part of the case rests on the translation being right.

E=mc3

Another clear sign of trouble is a statement that does not make technical sense. If the description appears to violate a physical law, or the logic that connects the phrases in a sentence escapes you, ask yourself whether it is more likely that the original patent or scholarly article was written by a madman with no knowledge of science, or translated by someone who did not understand it. Likewise, if you are reading within your field of expertise and have never heard of the techniques or equipment being described, it is unlikely that this is due to ignorance on your part. In the big bad world of international translation agencies, bilingual people without technical expertise are routinely asked to translate things they do not understand. And when the going gets tough, these translators wing it. Think of all the bilingual people you know. Now think about how many of them would be able to read and understand the science behind the documents you work with.

In the bad old days, when specialized technical translators were rare, attorneys got used to picking around the bad parts and filling in the blanks (for instance, guessing that when the translator wrote “acetic acid ethyl” they probably meant “ethyl acetate,” and working out from context that “turning current” referred to three-phase current). But even if you can make sense of such products of poor understanding, there is a very high chance that the meaning you take away will not correspond to the meaning of the original document. As with the linguistically challenged, translators who are out of their technical depth routinely resort to simplification and paraphrasing, and because the words they are attempting to reproduce have no real meaning to them, the result is much the same as one would expect from a person who did not know the source language. Remember that for every misunderstanding you spot, there are likely to be several more that you don’t.

Too Good to Be True

Oddly enough, another potential warning sign is an overly pleasant reading experience. This is due to a phenomenon in translation known as “smoothing,” in which a translator inaccurately rewrites the text in a way they find to be more pleasing than the original. An extreme example of this is a single patent claim rewritten as multiple complete sentences because the translator thought that would be easier for the reader to understand. You might also worry if the translation of an academic paper is free of technical jargon and run-on sentences. Smoothing is a type of interpretive translation and is not suitable for translations for evidence. When the cards are down, courts and patent offices care only about what was actually disclosed in the original publication.

Who Done It?

If you have your doubts about a translation on your desk, one route to reassurance is to check the provenance. If the translation has been certified or bears the name of the translation company, you know that the provider at least had enough confidence in their work to attach their name to it. Although certification is not a guarantee, it is a clue. If the translation is made by a translation agency, you can consider the reputation of the agency and the extent to which they specialize in your field. Personal certifications made by an individual translator may indicate that the person has worked alone, without review by a second translator, which may lower your confidence. Obviously, a grammatically unpleasant translation prepared by a foreign patent attorney or scientist deserves more confidence than a similar document coming from the desk of a student. When the origin of the translation is entirely unknown, particular care should be taken, as it is possible that the translator had no idea that anything more than a rough draft was required and never imagined that their work would land on an attorney’s desk.

Although most attorneys know this already, it bears mentioning that machine translations should always be subject to maximum scrutiny. In particular, while services that use statistical translation engines, such as Google and Microsoft, often read quite well, it is routine to find words, phrases, and ideas in machine translations that were entirely absent from the source text or, conversely, for the translation to be missing large chunks of what was originally there. For more information, see my discussion of why this happens and what to do about it.

Houston, We May or May Not Have a Problem

None of the above, however, should be taken to mean that every poorly written translation of unclear provenance must be thrown out. On the contrary, in many situations there are definite advantages to staying with an existing translation. If red lights do start flashing when you read a translation, all that really tells you is roughly how high or low your confidence level should be. As you may have guessed from the above discussion of smoothing, even a great sounding translation can be inaccurate and, by the same token, the chunkiest, most tortured writing sometimes gets the job done.

For an example of how translation errors can be decisive, look at the court’s findings regarding translation (highlighted) in Mitsubishi v Barr, in which Patent Translations Inc. was able to prove that a key prior art document did not disclose what a flawed translation seemed to show.

In the next installment of this series (March 2016), I will describe how to estimate the potential impact of a mistranslation and some good practices for getting a more accurate understanding of the fidelity of an existing translation. (If you can’t wait for the next installment, give me a call and I’ll be happy to tell you what I know over the phone.)