Translation Testing

A monolingual attorney’s guide to determining the accuracy of a translation

Patent attorneys may have concerns about the accuracy of a translation for any number of reasons. Your suspicions may have been raised by the warning signs described in the previous installment of this series. You may just have a hunch that something is not right. Perhaps the disclosure simply seems to suit the opposition’s case too perfectly. For that matter, if the translation makes or breaks your own case, even when nothing is obviously wrong, you will want to be sure that it will stand up to scrutiny. Remember that even simple transcriptional processes are subject to error (as can easily be seen in deposition transcripts, for example), and translation is a highly complex transcriptional process. While there exist best practices to find and eliminate errors, these are difficult, time consuming, and costly. Consequently, many translations include errors.

Should I Care?

A common factor in situations where investigation of the accuracy of a translation is warranted is when your level of confidence does not align with the importance of the translation. If the translation is one of a dozen documents supporting the idea that the art in question was known, it may not matter if this particular translation is reliable. On the other hand, if the translation is the only prior disclosure of the contested technology, then proving it wrong could be decisive for the case. In risk management terms, such a situation is defined as high probability plus high impact and deserves attention.

The issue of uniqueness vs. redundancy, applied in a slightly different way, is also key in evaluating the vulnerability of the translation to challenge. That is to say, if the description in question is repeated many times within the document, the chances of it having been mistranslated on every occasion are low. Interestingly, the chances of the translation being wrong are actually lower if the wording of the description varies from instance to instance. If, on the other hand, the disclosure rests on one sentence alone, the probability of impeachment will be much higher. For rather complex linguistic reasons, an even greater risk is encountered when two or more separate sentences in a translation must be considered together to arrive at the disclosure. When individual sentences from separate translations of separate documents must be considered together, the risk is very high indeed.

Remember also that the risk is the same even if the wording of the sentence at hand appears unambiguous. It is very common for the ambiguity inherent in a phrase written in one language to be lost when translated into another. That is not to say that it is impossible to maintain ambiguity when translating, but rather that it is easily overlooked. As a result, what appears cut-and-dried in a finished translation may have been much more nebulous in the source text.

Also, keep in mind that the tests for confidence described in the previous installment are general to the document and not specific to the sentence in question. That is to say, if the overall document contains problems of the types described, the fact that no such problems are found in one individual sentence should not increase your confidence in that sentence. Flawed translations are untrustworthy throughout, not only where the flaws are plainly visible.

What is true of sentences is also true of words. If an argument is going to rest on a single word used just once in the document, it makes sense to check if that word was actually used in the source text. Not only can disagreements arise as to the choice of an individual word, but it is, in fact, not uncommon for a word appearing in a translation to have no basis whatsoever in the source. I have been called on more than once to comment in cases that have advanced well past discovery, in which the supposed disclosure was based on a word that could not be found in any way, shape, or form in the original document; it had simply been added by the translator, who may have misread the original or imagined that they were being helpful by improving on what was actually there.

On the other hand, if a word is used multiple times, the chances of a corresponding term being found in the source text are very high. And if synonyms or equivalent descriptions are present, your confidence in the accuracy of the translation of that word should be higher still.

Looking Under the Hood

In the previous installment, we established a level of confidence for the overall translation. In this post, I have talked about the impact of potential errors and the vulnerability of the translation to challenge. Obviously, if you have low confidence in a translation that could have a large impact on your case, and this translation is highly vulnerable to challenge, further investigation is warranted. Regardless of which side is using the translation, you will want to know whether it is right.

Conversely, if your confidence is high, the impact is low, or the key point in the translation does not seem vulnerable (high redundancy), it may be best to leave well enough alone.

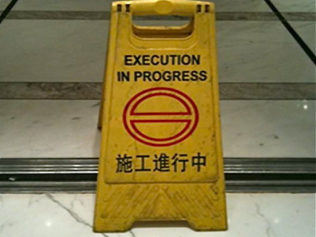

Ascertaining the accuracy of translations can be something of a Pandora’s box. This is because translations involve subjective judgment. I have written before about how the subjective nature of translations does not make them arbitrary, and certainly does not mean that we cannot know whether a translation is right or wrong. But it does mean that, starting with texts longer than about five words, it is extremely rare for two people to produce identical translations. So, for example, if you were to attempt to verify the questionable translation by sending the entire original document to another translator and comparing the results, you would then have two very different, and possibly contradictory, translations. What is more, you would have no basis for arguing that either one of them is right. Even if the gist of the key portion were the same, that would not tell you as much as you might imagine. The chances of two translators making the same mistake in a first pass translation are actually quite high.

Be Specific

We already know that genuine risks are essentially always limited to specific individual words or phrases, so it makes good sense to limit your investigation to those words or phrases. If you have any familiarity with the language in question, you may be able to confirm the translation of a single word yourself with a dictionary. Although I do not really recommend doing so, if you do use machine translation as an investigative tool, you are probably better off with a rule-based system, such as Systran (systranet.com/translate/), than with a statistical service, such as Google or Microsoft, for reasons described here. It is also a good idea to provide MT engines with the entire sentence and then, separately, just the phrase of interest. Keep in mind that the reliability of automatic translation decreases with the complexity of the sentence and the specificity of the technical context. If neither a dictionary nor a computer put your mind at rest, try a human.

A Friendly Call

As it may not be to your advantage to have written reports or emails saying multiple contradictory things about the translation, you may want to make your inquiries by phone. The obvious place to start is with the person who produced the translation. After decades of work as a translation editor, I can tell you that, when calling a translator, you will get the most useful information if you avoid putting them on the spot or on the defensive. As you can imagine, openers such as “Is your translation correct?” will meet with a predictable response. The best approach may be to let the translator know that the phrase, or word, is significant to your case, and so you are wondering if there are any other possible ways in which it could be translated. To get a well-considered response, put the question out there and then arrange another call at a later time for the answer. If the translator offers no revision to their translation, that should increase confidence, but you may still want to get a second opinion.

When doing so, or in cases where the original translator is not available, you will need to make a planning decision before approaching another translator. If you are sure that you will not be asking the person you approach to prepare a new translation of the document that will be submitted to the court or patent office, you may provide them with the existing translation and ask them the same questions you would have asked the original translator. Even in this case, remember to keep the questions open ended and give time for a response, especially if the translator you ask is not very experienced in this sort of thing. There is a tendency for people to immediately disagree with translations, just because the wording is different from the one that popped into their head. If they disagree with it on impulse, they may feel the need to stick with that position, even if, under other circumstances, they might have come to see the existing translation as a reasonable alternative.

If you go to someone whom you might later ask to produce a new translation of the entire document, then it is best to avoid any appearance of bias that might arise out of them having seen the other person’s work before they undertake their own. In this case, in order that they have the necessary context, you should provide the translator with the entire document, including any drawings, and direct their attention to the sentence, phrase, or word in question. Once again, indicate that you are interested in knowing if there is more than one way in which the words could be translated. The best translators will want time to reflect carefully on the most suitable translation, so it makes sense to schedule a call back for the answer. Once the new translator has formulated their opinion, you may wish to ask them to consider the existing translation with the same open-ended approach described above.

Now You Know

If the original translator changes their mind, or proposes a substantially different alternative translation, or if a second translator has a very different opinion regarding the gist of the original text, it is unlikely that the existing translation is correct. Likewise, if another translator agrees that the gist is as set forth in the translation that you already have, the existing translation is probably fine.

At this point, if you need to set the record straight, you will want to read the last part (March 2016) in this series. (If you can’t wait for the next installment, give me a call and I’ll be happy to tell you what I know over the phone.)